on margate sands . . .

” On Margate Sands

I can connect

Nothing With Nothing.

The broken fingernails of dirty hands.

My people are plain people, who expect Nothing. ”

~ ‘The Wasteland’, T. S. Eliot

The Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) heralds an unexpected duet following two and a half years of renovation. The refreshed third floor of Louis Kahn’s (1901 – 1974) sun-filled museum of planed wood, poured concrete and veiled Dutch linen is devoted to an orderly and mesmerising display of treasures by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 – 1851), highlights from Paul Mellon’s collection.

Yet visitors to the YCBA are welcomed into the impressive entrance foyer with a neon yellow script proclaiming ‘I Loved You Until The Morn Morning’ in a loose and slightly scribbled hand. This glowing remark or confessional statement is a fluorescent text piece by British artist Dame Tracey Emin (b. 1963). With the word ‘Morning’ first misspelt and crossed out, this artwork bears the title of Emin’s solo exhibition at the YCBA on the second floor.

Presented on a semi-industrial backdrop, Emin’s glowing fluorescent piece recalls sweethearts’ messages left in lipstick on a mirror, while the script itself the kind of graffiti we’d expect to see in school bathrooms or American locker rooms. A perfect spot for a cheeky selfie, this textural work of light also alludes to all the fun of the fair. Visitors from the UK may associate this piece with the sea-side vibe of amusement arcades, lighting up the esplanades of resorts all along the coast, gleaming like colourful pearls through grey mists and reflected in the ocean’s breath.

The nineteen large-scale paintings of Emin’s exhibition ‘I Loved You Until The Morning’ are autobiographical, referencing the artist’s recent battle with cancer as well as her experience of rape and abortion. Despite Emin’s exploits as one of the ringleaders of the Young British Artists championed by Saatchi in the ‘90s – along with her earlier controversial works ‘Everyone I have Ever Slept With’ of 1995 and ‘My Bed’ of 1998 – this exhibition demonstrates Emin’s commitment to painting.

ROMANCE & REALITY

Meanwhile, the ‘Romance and Reality’ exhibition follows the evolution of Turner’s work. In the 250th year of the anniversary of the birth of Turner it is only fitting that the largest collection of British art outside of the British Isles has opted to present a special exhibition of this master’s legacy.

We marvel at the extraordinary detail of Turner’s early works demonstrating the European influence of Claude Lorrain (1600 – 1682). His masterpiece ‘Dort or dordrecht: The Dort Packet-Boat from Rotterdam Becalmed’ of 1818, is a focus of this exhibition which also encompasses the artist’s only complete sketchbook located outside of the UK and a series of exquisite mezzotints. Finally, we are introduced to some of Turner’s later works, his seemingly abstract visions of light, smoke and water in paintings such as the somewhat amusingly titled ‘Squally Weather’ created between 1840 – 1845.

MARGATE, THE MUSE

However, during a visit to the YCBA, visitors may struggle to comprehend why Turner’s sublime works are presented in tandem with Emin’s emotionally charged canvases. Is it intentional that the Master of Margate is paired with our Dame, or it is merely a calendar cross-over? Although there appears little connection between Turner and Emin, even less to bridge the span of centuries, could it be that more than the salt streamed vista of Margate Sands unites this duo of exhibits?

Turner declared the skies of Thanet to be the ‘loveliest in all of Europe’ and this perhaps helps to explain his frequent visits to Margate. Within easy access of London, first by boat and then by train, Turner’s ‘love affair’ with this Cinque Port began in 1786. Aged 11, Turner was sent to live with his uncle, a fishmonger in the seaside town. Turner attended Thomas Coleman’s School until 1788; a Blue Plaque celebrates the formative years Turner spent here. Later, in the 1820s, Turner would make frequent visits back to Margate, staying at The Ship Inn owned by Mrs Sophia Booth.

Situated on Cold Harbour, Mrs. Booth’s guesthouse offered direct views of the expansive skies and sea. The Turner Contemporary museum, by David Chipperfield, was built in 2011 and is located on this very site. Following the death of Mr Booth, Turner and his landlady became long term companions. Local artist Ann Carrington’s sculpture ‘Shell Lady’ has looked out from the esplanade to the sea since 2008 – not only a nod to Margate’s mysterious shell grotto beneath its streets, but a meaningful tribute to Mrs Booth and her love for Turner.

The small watercolour simply titled ‘Margate’ from the series ‘Picturesque Views of the Southern Coast of England’ is displayed in the ‘Romance and Reality’ exhibition. This detailed watercolour demonstrates Turner’s deep connection with the town. Beneath an Azul sky of sprawling transparent clouds – a blue echoed in the cobalt patina of Carrington’s sculpture – the slight arc of the Georgian seafront frames the harbour and scores of men hauling a shipwreck onto the sand.

You can spot windmills and the lighthouse on the Harbour Arm, which still stands today, whilst another merchant ship seems to lurch in the shallow water of the Bay. To the left, tall chalk white cliffs appear on the horizon, almost like the cliffs at Botany Bay, perhaps revealing Turner’s artistic license in this maritime scene?

The crumpled sail of a stricken ship appears strewn across the tideline. Saturated with brine, it lies like the scaly skin of a dead sea monster as the wreckers hastily salvage the galleon’s goods. Turner may have been illustrating the risks taken by sailors and merchants as they ensure the amenities expected by middle-class visitors are readily provided, thus hinting at Margate’s status as a fashionable destination. The seaside town is forever captured by Turner’s brush, the scale of this piece reminiscent of a sepia photograph. A historical moment captured in paint for William Bernard Cooke’s special publication.

'MAD TRACEY FROM MARGATE'

Like Turner, Emin was also born in London. She grew up with her twin brother Paul in Margate where her father owned a hotel on the seafront above the Winter Gardens. A manipulator of her own public image, Emin’s mythology as an artist is intertwined with Margate, as expressed in her 1999 ‘Mad Tracey From Margate’ documentary and memoir ‘Strangeland’.

A sense of nostalgia radiates from Margate; a postcard vision of Georgian charm pasted over with violence and decline parading as glamour. The town’s recent seedy seaside past – the once salubrious esplanade adorned with a beguiling clocktower and lido, awash with sex shops, anti-social behaviour and brash vulgarity – is synonymous with Emin’s own self-invention. Her boozy self-parody may be considered akin to that of Andy Warhol’s cunning act. Margate is more than just a muse to Emin. Margate is paramount to Emin’s identity, her raison d’être as much as her ability to place the spotlight on herself. Margate is Emin.

For the most part, the works included in ‘I Loved You Until The Morning’ depict lone females in crawling, sitting or standing poses. Whilst the figure’s face is scrubbed out in ’Black Cat’ these females often seem unaware of the viewer, their gaze cast down at the suggestion of blood pouring form their bodies. They often seem caught unawares, such as in ‘I wanted to Be Clean’ where a nude figure stands under a shower spouting a red shroud enveloping the nude as though the membranous outline in a Medieval Icon. This perhaps contributes to the unsettling sense associated with these paintings; have we unintentionally stumbled upon the figures during very personal and emotional moments or are we creeping up and spying on them?

In a slightly similar fashion, Turner’s figures are depicted absorbed in various activities. His great merchant ships often seem to sail off into the distance, almost dissolving into the luminous seas and skies of the artist’s vision, off into the very weft and weave of the canvas itself.

Emin’s painting ‘A Rose’ was once fondly titled ‘Turner Eat Your Heart Out’. Emin’s use of impasto and layers of thin acrylic creates an almost snowy appeal. The effect becomes synonymous with Turner’s atmospheric effects on the 3rd floor. However, there is a sharp jolt of red remaining from an earlier stage of the painting process. This appears like a stuck out tongue – an allusion to a sexual act – or indeed a fragile rose petal, swirling in a mist-clothed garden.

Taking centre stage, this smear of red may recall Turner’s antics at the Royal Academy in 1832. To the astonishment of the crowds Turner added a bright red buoy to his cool toned ‘Helvoetsluys Seascape’ so as not to be upstaged by Constable’s cadmium rich bridge scene hanging in close proximity. This moment is interpreted to great effect by Timothy Spall in Mike Leigh’s 2014 film ‘Mr Tuner’. The addition of the red spot brought Turner’s entire seascape into new focus and it certainly seems like Emin was inspired by this story! Here, her reference to Turner is a playful one, welcome light-hearted relief from the frankness and unsettling honesty of some of the other paintings presented in the exhibit.

‘A Rose’ indicates there may be more at play between the ‘Masters of Margate’ than just the time each artist has spent in a historic fishing town. ‘Romance and Reality’ juxtaposed with ‘I Loved You Until The Morning’ enables us to see how Turner’s painting technique and ability to make a statement has inspired Emin – a factor which certainly could have been emphasised in the contextualisation of these con-current exhibitions.

ALLURE OF aMERICAN ABSTRACTION

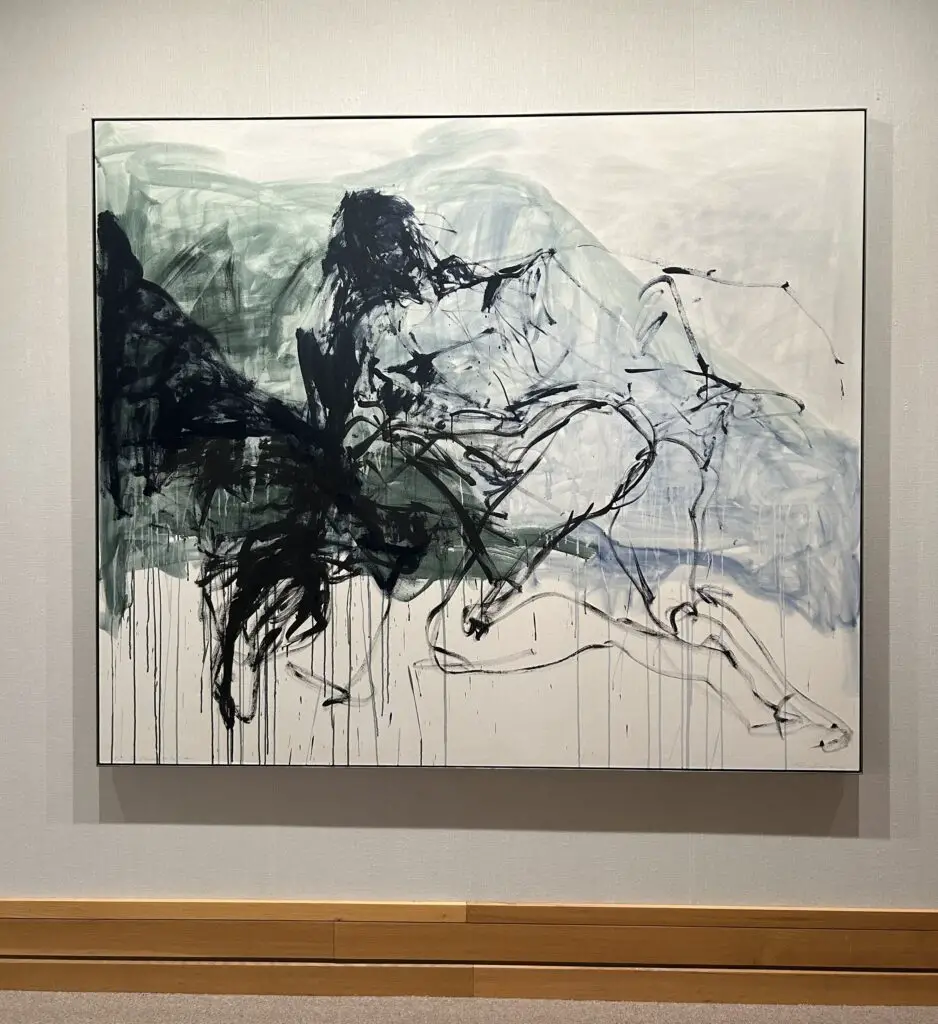

We are perhaps caught a little off-guard by Emin’s ‘From the Mountains to The Lake’. With no hint of red, this work strikes a different chord. It is as though the female form becomes the landscape, the light watery wash reminiscent of Turner’s thin layers of glaze, echoing how he would often thinly apply oil paint as though handling watercolour. Whilst the limbs and buttocks of Emin’s figure are outlined in deft brushstrokes, the upper body merges into the landscape beyond.

Meanwhile, the title of this work may reference the American abstract painter Helen Frankenthaler’s (1928 – 2011) ‘Mountain and Sea’ of 1952 – an interesting interpretation considering ‘I Loved You Until The Morning’ is Emin’s first Museum show in the United States. Mountains are often associated with transcendence and the notion of receiving a ‘higher wisdom’. Emin’s figure appears to crawl towards this vision, perhaps emerging from the depths of a lake and the tangle of pondweed to the majesty and serenity of the mountain; is this the artist on her own journey towards enlightenment?

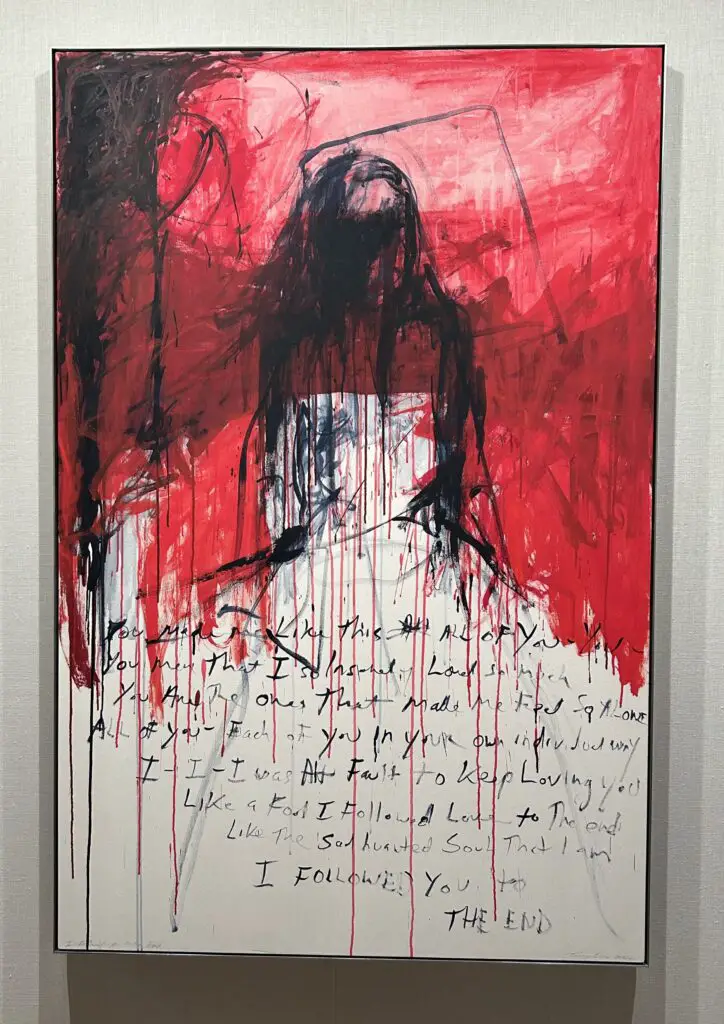

But it is not just echoes of Frankenthaler we see in Emin’s paintings. Undoubtedly there is a strong connection to the work of American artist Cy Twombly (1928 – 2011). From Emin’s whitewash effect and colour palette to her definite – confident – brush marks, there is a strong resemblance to Twombly’s own paintings inspired by Greek classicism. Even the text embedded into Emin’s canvases, sometimes half hidden behind ghostly layers of paint, as in ‘I Followed You Until the End’, where the bride’s dress becomes a sea of prose, reminds us of the daily ritual of ‘journaling’ and can be considered a direct reference to Twombly’s own inclusion of written prose.

With influences of Frankenthaler and Twombly alongside inspirations of Turner, it’s clear that ‘I Loved You Until the Morning’ has been curated with the expectations and visual language American audiences can readily connect with. This enables a sympathetic reading of Emin’s work and her personal struggles in spite of her ‘Mad Tracey of Margate’ persona.

POETRY & PROSE

Writing is an integral part of Emin’s practice and the special publication for Turner’s ‘Romance and Reality’ exhibition contains a fold-out love letter from Emin. Almost like a secret pact between the two artists, Emin emotionally, melancholically, writes about the magnetic pull of Margate, its ‘grey sky’, ‘Prussian blue deep’ sea like ‘walking on flat ice cold sand’. A beautiful and meaningful way to tie these two exhibitions together, it would have been more impactful and successful if Emin’s ‘Love Letter’ was actually part of the display rather than hidden in the gift shop.

Despite T.S Eliot’s (1888 – 1965) belief that he cannot connect one thing to another on Margate Sands, it seems that both artists transform intense personal experience into paintings with universal appeal. Eliot composed a section of the ‘Wasteland’ whilst taking refuge from the bright sun at the Nayland Rock shelter along the seafront at Margate and presents us with a fragmented, fractured vision of civilisation. Margate appears as a broken and dysfunctional place in his portrayal of declining human history. An abandoned place where nothing quite adds up. However, it would seem that the work of Turner and Emin does share a common spark, a thread of connectivity across two centuries.

SOAP SUDS

Turner’s dramatic painting ‘Staffa, Fingal’s Cave’ is another highlight of the ‘Romance and Reality’ exhibition. We are presented with the artist’s personal experience of Scotland’s infamous caves, the ancient geological marvel of vertical basalt stacks glowing in the sunset as a reminder of its volcanic origin. We can almost hear the wistful melody of Mendelssohn’s (1809 – 1847) ’Overture from the Hebrides’ or ‘Fingal’s Cave’ as we take in the scene. With the timeless appeal of the low-lying sun and geological wonders, there is a sense of spiritual connection to the Natural world – the clouds appear to part as if a divine light radiates from the saturated sky.

These towering clouds dwarf the silhouette of a steamship which most likely brought visitors such as Turner to this very site. However, soot and smoke belch from the ship and stain the sky as though in an effort to rival Nature’s own creations – a symbol of the Industrial Revolution. The first work of Turner’s to have entered an American collection in 1845 when purchased by the New York collector James Lennox, Turner almost prophesies today’s climate change crisis.

Once derided by critics as ‘soap-suds’, Turner’s 1845 oil painting ’Stormy Sea Breaking on a Shore’ captures the moment a single wave crashes across the horizon, sending spray flying through the cloud-thronged air. We can almost taste the salt on our lips and feel the cool brush of the wind as we study each fleck of froth. Bemusing critics and the public alike, Turner sought to faithfully render the grandeur and power of nature, rather than offer a beautified or purely romanticised version. The turbulent layers of paint show a deep sense of respect for the wild, uncontrollable power of the sea, whilst hinting at human frailty and insignificance.

Meglip may have been added to provide a sculptural quality to the piece, though evidence of this would have been lost during early restoration work. The painting would have been completed around the time that Turner is believed to have tied himself to the mast of a ship for four hours to experience stormy conditions firsthand. This act of extreme research enabled Turner to find a universal truth in this personal experience – we can only imagine how terrifying this must have been!

However, as an unlikely feat for someone in their sixties, no solid evidence has been found to confirm Turner’s experiment. Either way, this famous narrative of British art history does set Turner apart from his contemporaries. Is this story an act of self-mythologising? An added layer to a life lived in paint? A strategic way to bolster the critics’ claims that Turner was a madman?

MASTERS OF MARGATE

Both exhibitions remind us that painting is always full of stories. As the great ecological emergencies of our time plunge us into a challenging and uncertain future, Turner’s paintings are a stark reminder of the beauty, the power of Nature and the natural world upon which we rely.

As we watch genocide unfold in the middle east, Emin’s exhibition also comes at a crucially timely moment. Her use of red becomes the blood and gore, the pain and suffering of war as well as a record of personal trauma. In ‘You kept It Coming’ a female figure crawls on her hands and knees as though through an abyss. Do we feel helpless in front of these works? We may wish to run up and embrace Emin’s figure, vulnerable and alone, or blot out the toxic smokestack beside Turner’s Fingal’s Cave, to save humanity and Nature from the trauma of the brush.

At a time when the very principles of democracy are threatened and the rights of women are eroded and curtailed, it is admirable that the YCBA has staged this exhibition of Emin, an artist who has very publicly shared her experiences of having an abortion. The abortion, of course, being the very birth of Emin’s art practice – her gift to us – rather than becoming as she once put it, ’another single mother’.

Viewed in its entirety ’I Loved you Until the Morning’ could be considered a transfiguration of the artist’s 1998 unmade bed: strewn panties transposed into poetical prose; the dribble of an empty vodka bottle now the drops and drips of paint. Creased and crusty bed linens resurrected as scrubbed brush marks of generous layers of acrylic. The imprint of the artist’s own body, once laid amongst the detritus of pain and turmoil, is now present in the form of Emin’s own fingerprints and faint signature – displayed at the bottom of each work in light pencil. If Emin’s bed was the cocoon for a moth drawn to the flame of fame, these canvases are chrysalides for a kaleidoscope of butterflies. A metamorphosis of rebirth. We witness figures struggling to emerge from the paint, female forms being born from the womb of violence and loss into the realm of the spirit.

The turbulence and frantic brush marks of Emin’s nudes also allude to the moody, atmospheric effects of Turner’s paintings. Figures crumple like the clouds above Turner’s landscapes; pools of blood spread like the glowing light in sunset depiction. Emin’s emotional works mirror the weather and the tension of Turner’s paintings, possibly highlighting our human connection to the natural elements of sea, light, sky and air. An expression which is perhaps physically experienced in a place such as Margate, where expansive skies meet a seemingly endless spread of sea.

With the success of ‘Mr Turner’ (though not actually filmed in Margate but Cornwall’s Kingsand) surely it will soon be Emin’s turn to make her debut on the silver screen? After all, Emin’s story has it all – rebellion, trauma, a dance with death and the hope of an incredible recovery. Furthermore, Emin’s story even offers An American Happy Ending, of candy cotton fuzz as she becomes a ‘hometown proud’ pillar of the community of Margate.

Pouring their lives into their work, both Turner and Emin somehow ‘fit’ our ideals of what an artist should be. Visionary, daring and generous in spirit.

At the time of his death, Turner bequeathed over 100 finished paintings, almost 200 unfinished works and around 20,000 sketches to the British public. Emin of course has established her Foundation, two artist residence programmes, the TKE studios as well as gifting properties to local businesses in Margate. She has been largely responsible for the uptick of cultural flair the town currently has to offer. With its entertainment park ‘Dreamland’ riffing off the United State’s Coney Island, Margate is now a place for dreaming, for cultural connections. A muse rising from the ashes of its own nostalgia.

Only in the USA is there the cultural foresight for such an exciting duet of exhibitions. This con-current spark of curatorial brilliance illustrates how the YCBA is already leaving the political and identity concerns which have befallen the art world of late. Displayed in tandem, the work of Turner and Emin reveals how Britain’s painting legacy continues to go from strength to strength.

PENDOUR PICKS